As harvest kicks into full gear, wine country will shortly come alive with talk about optimal ripeness, brix levels, and pH. What most vintners are essentially striving for is a balanced crop. But the word “balance” has become a rather polarizing topic in the wine industry as of late. Everyone seems to be ‘in pursuit’ of it in one way or another – but the definition of what constitutes ‘balance’ depends on the source and philosophical stance.

Alex on the vineyard taking grape samples to test for brix levels & pH balance

Of course balance can refer to any number of factors, and savvy wine consumers are beginning to adopt the industry lexicon, demanding specific levels of residual sugar, alcohol, tannic structure, acid and viscosity. One important winemaking concept has so far eluded the mass consumer market is the idea of pH. But talk to a serious winemaker, and one gets the impression that pH is perhaps the most critical factor to nearly every aspect of a wine, from flavor, to color to age-worthiness.

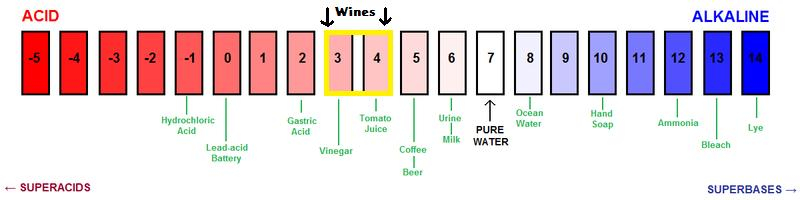

Many people understand pH from their high school chemistry classes: The pH scale technically is a logarithmic scale that measures the concentration of free hydrogen ions in a given substance. The general scale used to measure pH goes from 0 to 14 with neutral fluids being at 7.0. Most wines fall between 3.0 (roughly where vinegar falls on the scale) and 4.0 (the pH of tomato juice). To provide context, coffee and beer tend to fall around 5.0, while milk is at 6.0.

According to wine maker Alison Crowe of the award-winning winemaking blog The Girl and the Grape “pH is the backbone of a wine”. This time of year, when vintners are sampling their grapes daily and beginning to formulate their decisions on when to pick, they are really only looking at two numbers: the brix reading (on sugar levels), and the pH number.

The two are actually somewhat related. Unripe grapes have low sugars and high acid levels (and thus low pH levels). As the fruit ripens, sugars increase and acid levels decrease (thus increasing pH). An over ripe grape will have very low levels of acid, while tasting very sweet.

Here is where winemakers can play with style, especially when it comes to red wine, where pH levels are slightly more important due to the additional role of the grape skins. The general rule of thumb states that the earlier one picks grapes, the higher toned the fruit-flavors will be in the finished product, with a more mouthwatering structure due to the higher levels of acid. However, wines can often taste too tart or astringent if the pH is too low for the sugars to compensate.

If grapes are picked later, the resulting wine’s flavor profile will tend to provide more brooding, dark fruit notes with a fuller, richer mouthfeel and structure. The danger here is that wines can prove syrupy and heavy on the palate if care isn’t taken to mitigate the sugars and alcohol with enough acidity to give the wine some needed lift.

In Europe, grapes often cannot ripen past a certain point before encountering mold, due simply to the natural weather patterns. Wines therefore cannot (in most years) achieve the same sugar and pH levels as easily their California counterparts.

Heidi Barrett in her element

In the 1960s and ‘70s, winemakers in California had to experiment. As farmers of a relatively new region, they really only knew European styles as a model of taste and style. But in the 1990s, and early 2000s, given our growing conditions in Northern California, intrepid vintners began to play with slightly higher pH levels in order to create wines that might be more enjoyable (and drinkable) on release. Innovators like Heidi Barrett, John Kongsgaard and Helen Turley blazed the trail. Jeff Smith from Hourglass Winery in Calistoga grew up in Napa and chronicled first hand this dramatic shift. He notes how “they unlocked a whole new world and redefined the spectrum of California wine”. Suddenly, wines that were once impenetrable before 10 years of cellar aging could be enjoyed immediately upon release.

One influential critic in particular was a huge fan of this style, and his 100-point scores came to define the market. Winemakers took note and began to think of high pH winemaking paired with high brix levels as a formula for success. And for many, it was. After all, that much concentration and flavor can yield blockbuster wines of explosive drama.

However, as stated, this can really only be done successfully if the conditions are right and the acidity persists – there is a huge potential for failure. Many wines made in this way are perceived as flabby, with no energy or verve. Peter Mondavi Sr., legendary proprietor of Charles Krug, calls such results “cocktail wines” because they rarely elicit the desire for a second glass. Wines from the ‘90s and early 2000s with finished pH levels over 4.00 continue to prove that their potential to age is a mixed bag. Some have aged gracefully and some have fallen apart.

These styles quickly lost esteem among discerning oenophiles who grew impatient with such heavy, character-less wines. Also as cult wines from Europe became untouchable in many ways to the average collector, fans of Californian ultra premium wine turned west to seek out age-worthy wines. The almost imperceptible acids in far too many poorly made Cabernets meant that they couldn’t stand up to nearly as much aging as their predecessors. The wine cognoscenti retaliated by swinging the pendulum sharply in the other direction. Suddenly a new trend began to emerge – low pH winemaking.

The last five years have seen tart, high acid wines become all the rage for a young, anti-establishment group of vintners and drinkers and groups have now formed around concepts like alcohol levels under a certain threshold, and picking at a specifically low level of brix. Such practices are meant to achieve a ‘freshness’ that higher pH wines couldn’t seem to maintain. It remains a popular, edgy, concept, especially with regards to Burgundian varieties like Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, whose subtle characters had become slightly bastardized due to their popularity (a double edged sword brought on by Sideways!) and subsequent prescriptive winemaking. One cannot apply the ‘100-point’ model to wines that require a more nuanced approach.

The problem with this anti-establishment model is that it doesn’t vocally distinguish its standards between grape varieties, and Bordeaux grapes simply don’t taste good when they’re intentionally picked under-ripe with low-pH levels. So how is a Napa Cabernet producer meant to compete with the hipster wine set when the conversation around the definition of balance has been dominated by a group of earnest Pinot growers? After all, when compared to Pinot Noir, any variety over 3.55 would be considered a high pH wine. However even the most balanced Rhone Syrah can have a finished pH over 4.00, so the broad brush simply cannot and should not be applied.

If ageability is the argument in favor of this trend, wines from the “food wine” era of the ‘70s and early ‘80s are showing us now that wines with excessive acidity and extremely low pH (3.40-3.50) are not really proving pleasurable to drink at 30+ years of age. They are interesting case studies to be sure, but as one winemaker puts it, “most of the fat has melted away and left a jagged bony skeleton”.

Jeff Smith and his seasoned winemaker at Hourglass, Tony Biagi, are among an activist group of thoughtful vintners trying to dispel the idea that high pH equals unbalanced, lethargic wine. Jeff defends high pH winemaking, arguing that it was too easily dismissed. He believes more experimentation is needed in order to make wine at that threshold while preserving a wine’s vivacity. For example, he has discovered that “energy comes from not just acidity, but an understanding of minerality”.

Tony Biagi (left) & Jeff Smith (right)

Jeff and Tony believe that it is possible to make wine at a high pH if the grapes come from a high mineral site. Minerals get ionized and positively charged during fermentation, much like what happens to a battery: as they get more volatile, the minerals will work with the salivary glands on the palate to produce a mouthwatering effect. This compensates for any acid that may have been lost, while preserving a level of freshness that helps keep the fruit tasting fresh and lively.

Tony has found that a finished pH in the 3.68-3.90 range can deliver a wine that proves round and lush upon release but has enough verve and acidity to age gracefully. The most important factor though, and the final arbitrator of acidity level, should be taste. Tony says, “Dogma works either way. You can say that all wines are good and age able at a high acid range or all wines are bad at a low acid range. I believe the best test is to taste objectively and if it is what you want and pleases you then it’s balanced.”

Like the discussion of ripeness in general, the pH pendulum went from the left to the right extremely quickly over the last three decades. Winemakers like Tony and Jeff, as well as other talented vintners like Matt Courtney, Frederik Johansen, Thomas Brown, Aaron Pott and Mary Marr are trying to pay homage to the visionaries who came before them, while carving their own path when it comes to pH.

Most would argue that the pendulum is settling comfortably at the center-right (towards 4.00), but that taste, over dogmatic slavery to a number on a scale, should be the arbiter. As Biagi puts it, “There is no more recipe winemaking”.

All the Swirl is a collections of thoughts and opinions assembled by the staff and industry friends of Charles Communications Associates, a marketing communications firm with its headquarters in San Francisco, California. We invite you to explore more about our company and clients by visiting www.charlescomm.com.